June, 1991. Wellfleet marked its five-year anniversary since the closing of the founding funding. We had a large outdoor celebration with most of the company’s employees in attendance. A lot of beer flowed, plenty of food was devoured, and the atmosphere was a mixture of satisfaction and anticipation. We had a lot to celebrate – the company was profitable, revenue was growing exponentially, hiring was becoming a bigger focus for management, and we were contemplating becoming a public company. Soon.

As usual, Cisco was a year ahead of us, having issued their initial public offering in February, 1990. Their market capitalization at the time of their ipo was $224M. [As of 30 September 2024, Cisco’s market cap is $198.6B]. For 1990, that was a more than respectable valuation. When we started Wellfleet in 1986, Sev and I thought that we would have achieved success if the company valuation reached $100M. In much of finance, all things are relative. Interlan was acquired in 1985 by Micom Systems for stock valued at $62.5M at the time of the closing. Creating a new company in the next six years with a value that was 60% higher than Interlan seemed like a real win. However, clearly, we did not have accurate insight into the potential size of the market for routers.

Beyond the beer and the celebratory mood, there was eager anticipation on the part of everyone in the company in taking the company public. Every Wellfleet employee either owned stock or was holding stock options at or below the June, 1990 “strike price” of $1.90 per share. Making the stock “liquid” meant that several millionaires would be created overnight. It created an electric atmosphere for everyone in the company. What none of us knew was just how quickly the ipo would arrive.

Steve Cheheyl was hired by Paul as the company’s new CFO in January, 1990. He had considerable experience in taking technology companies through the ipo process, and subsequently managing those companies as public entities. He was known as a no-nonsense, lets-get-this-done type of leader. Charisma wasn’t in his vocabulary. And Wellfleet didn’t need charisma. We were about to chase Cisco in the financial markets, not just in the product markets. It would be another slugfest.

Prior to Steve C’s arrival, numerous investment bankers had been wining-and-dining Paul in an effort to win the ipo business. Early in his tenure as CFO, Paul told Steve that the company was ready to go public. Because the bankers had told him so. Steve thought otherwise. He decided to throw himself in front of the Sev bus. He told Sev that he didn’t think so, there was still a lot of work ahead in terms of preparing the company to be public – better sales forecasting, staffing for investor relations, tighter budgeting and spending controls, etc. Sev backed off. Steve survived his first confrontation with his new boss.

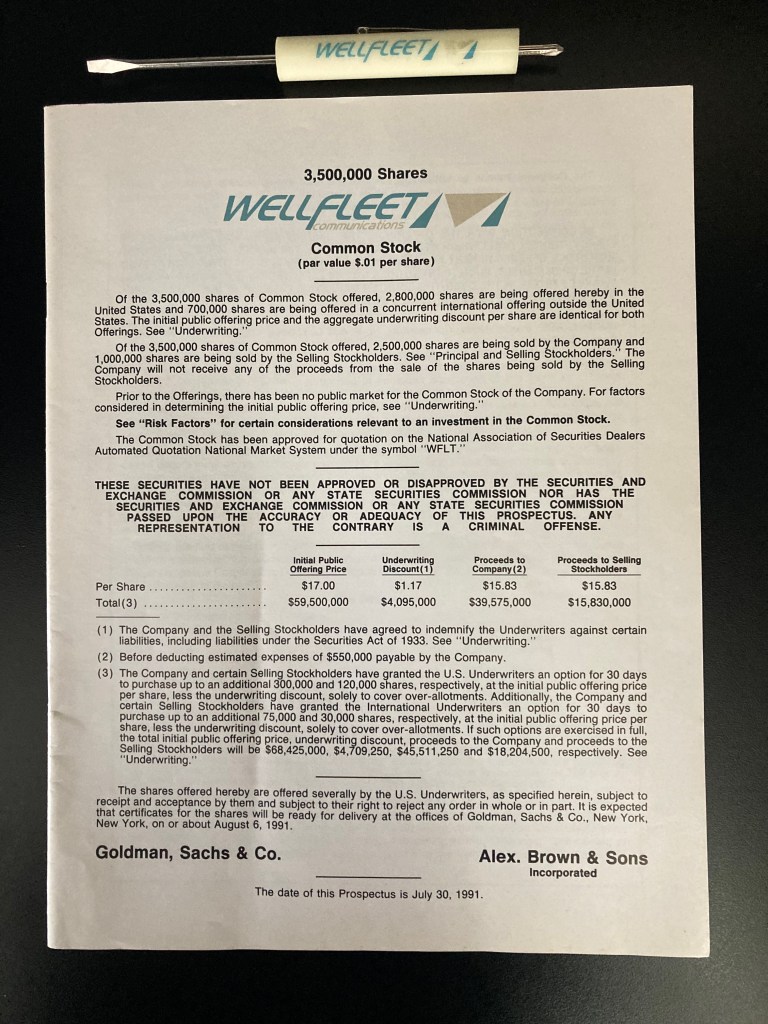

Ultimately, Sev and Steve Cheheyl recommended to the board, who subsequently approved, two lead investment banks – Goldman Sachs and Alex Brown & Sons.. A team of bankers, lawyers and accountants was assigned the task of drafting the prospectus. The purpose of a prospectus is to provide prospective buyers of Wellfleet shares information concerning the company’s core technology, products and services, market segments, risk factors, management roles and responsibilities, and financial results to date. The management committee was assigned the task of reviewing the draft prospectus, offering comments and corrections where appropriate.

My initial reaction to the draft prospectus was one of disappointment. The sections describing our technology, products and markets – most of the document’s prose – was cut and pasted from our existing marketing materials, some of which was dated, light on some potentially important technical details. I went to Sev to express my disappointment, but more importantly, I offered to rewrite the sections dealing with our technology and product descriptions. He agreed that those sections were deficient and gave me the green light to submit my rewrites.

To me, the most important concept to get across to a prospective investor was that of our products’ system architecture. I felt that Wellfleet’s “loosely-coupled multiprocessor” system architecture was our one true competitive advantage over every other competitor, including Cisco. It was true that Cisco’s products had an advantage in terms of software features and functions. For some time, our sales and marketing messaging emphasized our system architecture as the rationale for our customers making a future-proof investment in a critical element – routers – of their enterprise networking architecture. Increasing “speeds and feeds” required robust scalability, reliability, and performance throughout their network. We felt that Wellfleet was unsurpassed in those dimensions, while future software releases would provide a growing list of features and functions. Furthermore, future hardware generations that provided higher performance would not obsolete our system architecture nor most of the current hardware.

It seemed a pretty compelling story that needed to be accurately depicted in the prospectus. But it wasn’t told in the bankers’ initial draft. So I ignored most of what had been written by them and set out to write my version of Wellfleet’s technology and products. Describing any technology product in plain English is not an easy task, so it took me a while to create my initial draft. By the time I submitted it to Sev and Steve for their review and approval, I was pretty happy with the result. With only minor edits, it made its way into the prospectus. It was gratifying to contribute to the ipo process in this way. I was quite proud of my attempt at explaining a technologically challenging topic to who I imagined to be an experienced technology investor. I thought that my part in the ipo process was finished. It wasn’t.

A week or so later, Sev came into my office late in the day to tell me that the ipo team was having a difficult time coming up with a four-letter stock symbol for Wellfleet’s NASDAQ listing. I hadn’t given any thought to that whatsoever. While listening to Sev rattle off a list of symbols that were suggested by the ipo team – all of which had been registered by other companies – one idea came to me. Eliminating every vowel in our name, and focusing on the second syllable, I said “I think that is an easy one. We should list our stock under the symbol ‘WFLT’. What do you think of that?” He went to find a copy of that day’s Wall Street Journal, and came back to declare “Its not currently listed on NASDAQ, I think that’s it! I like it!” My second contribution to the ipo process. I was pretty proud of that one too.

Steve and Paul took the show on the road, hitting the major financial centers in the US and in Europe. They told an impressive story in their typically flashless, low-key, fact-filled style. Steve Cheheyl had successfully taken Applicon and Alliant Computer, pioneering startups in their own right from the 1970s and 1980s. He was on his way to leading WFLT to the listings in the back of the Wall Street Journal.

Wellfleet’s initial public offering launched on August 1, 1991. The board had set the price at $17 per share the night before. The first trade occurred at a price of $21, and the stock closed at $23.

In the following days and weeks, several predictable phenomena could be observed. Steve Willis, wearing a new Hawaiian shirt, was walking the halls with a copy of Wall Street Journal under his arm. Our parking lot was witness to the arrival of several shiny new (and used) cars. I bought a used Mercedes-Benz 300E. Gary Bowen treated himself to a new Lexus LS400. Some of the engineers purchased new cars. None were exotics.

One day, one of the investment bankers dropped by to have a chat with Steve C. The i-banker was curious to see how our parking lot population had changed, particularly among senior management. Steve guided him outside, pointed at a 1960s vintage red Oldsmobile 442 and said “That is Sev’s new car. And that old pickup truck next to it? That’s still my work ride.” Steve thought the i-banker was surprised that we didn’t follow the Silicon Valley custom of running out to the Ferrari and Porsche dealers on day ipo+1.

The employee stock watching had started. And a financial rocket ship had lifted off.

Leave a reply to mark canha Cancel reply