The center of commercial activity for the nation has been New York City since the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825. By then, New York had surpassed Philadelphia in imports and exports, but the center of banking was the Second Bank of the United States chartered in Philadelphia in 1816. Being the only federally chartered bank, the Second Bank exerted its influence over every state bank, creating the template for today’s banking regulations. The Philadelphia Stock Exchange, established in 1790, was overtaken by the New York Stock and Exchange Board (later, the NYSE) by the 1830s.

Fueled by the entrepreneurial spirit of the immigrants arriving daily in New York, speculation in call options kept New York’s finance industry awash in liquidity. Risk-taking became the norm among stock traders. The failure of Second Bank to renew its charter in 1836 paved the way for New York banks to become the country’s leading financial institutions with the passage of the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864. The corner of Wall and Broad Streets became the home of the New York Stock Exchange in 1865. The nation’s most influential banks and brokerage firms crowded around Wall Street, giving momentum to cementing New York as the financial center of the nation.

Wall Street has provided a target-rich environment for technology firms since Thomas Edison popularized the use of the stock ticker in 1890. Telegraph wires were used for transmitting stock prices directly from trading floors to the offices of bankers and brokers throughout the city of New York in near real time. The “ticker tape” displaced the use of telegraph couriers, boys as young as 12 years old, for delivering pricing information and trade orders.

This made trades much more precise by dramatically reducing the delay in effecting transactions between buyers and sellers. By 1890, the telegraph companies supplying pricing information to the bankers and brokers were bought out to form the New York Quotation Company to provide uniform pricing data to all of their customers.

Technological innovation by Wall Street evolved with the adoption of the telephone that allowed investors, banks and brokers to speak with one another in real-time to make trades. Pricing information, however, was still slowed by the need to manually record transactions, then put them out on the ticker for others to see.

By 1920, there were 88,000 telephones installed in the Wall Street district. In 1929, the NYSE centralized a system of bid/ask pricing which had the effect of increasing the volume and efficiency of the market. A high-speed ticker service was introduced later that year – which may or may not have to contributed to the crash in October.

During the years leading up to World War II there was not a lot of innovation on Wall Street. Certainly the Great Depression (1929-1941) had a profound dampening effect on the adoption of new technology on Wall Street and throughout the economy.

After World War II, the federal government tightened the rules around the use of credit for buying stock, initially insisting that buyers put up cash for 100% of the purchase price. Later this was reduced to around 70% which allowed traders to use “margin” accounts to finance a portion of their buys, using stock in their accounts as collateral for loans.

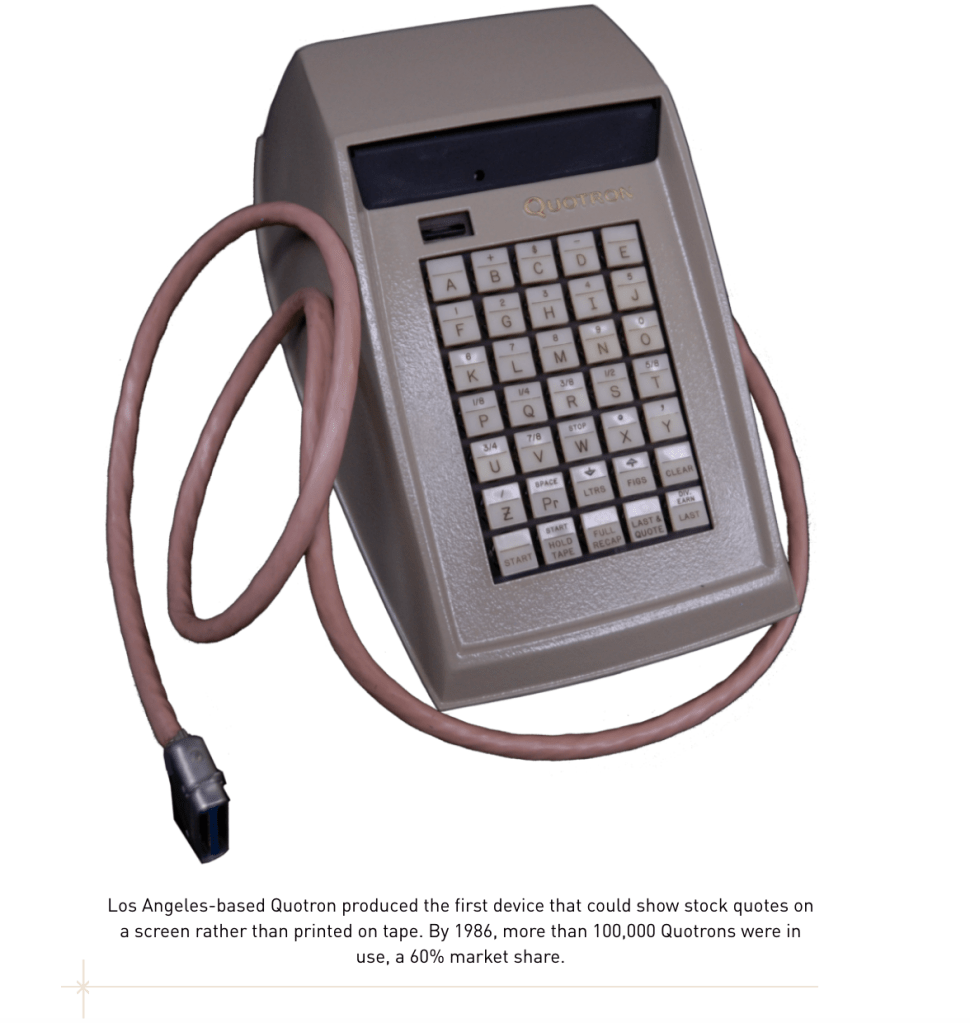

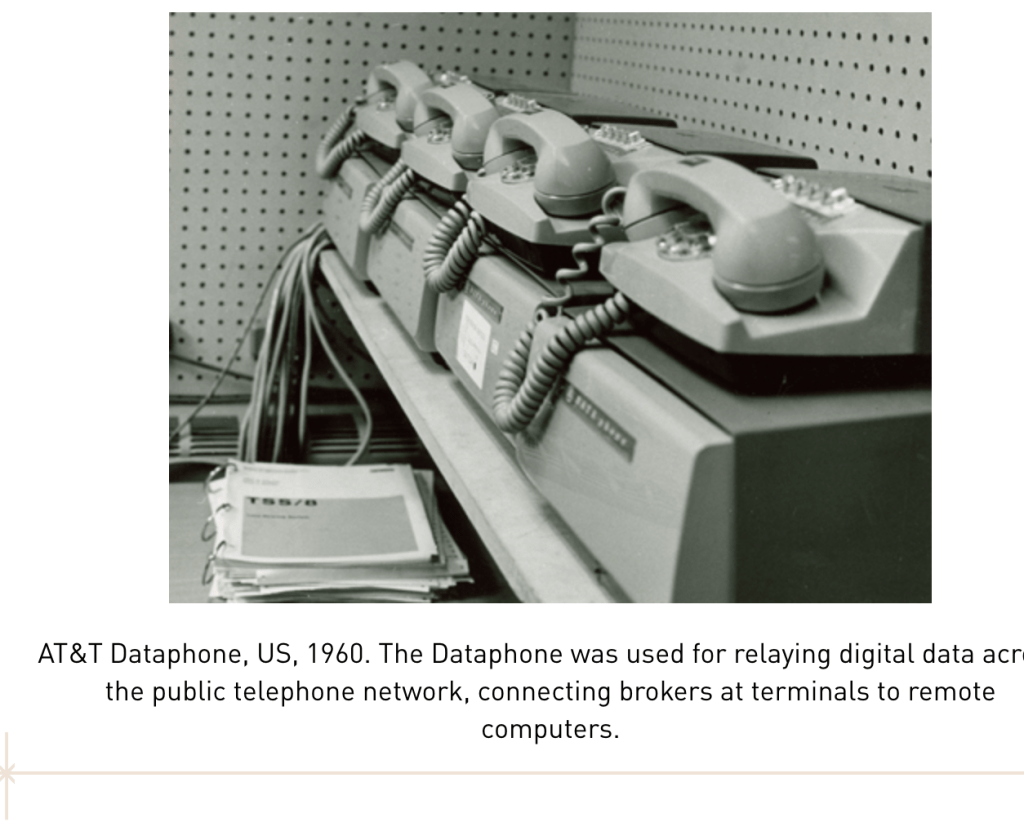

In 1960, the Quotron electronic stock ticker was introduced and became an instant hit on Wall Street. Traders were able to type in a stock symbol and receive the latest up-to-date bid/ask price. The Quotron system grew rapidly which required the computer systems to which they were connected to also grow – four networked CDC-160A computers. Access was through AT&T Dataphone modems, which numbered over 100,000 by the mid-80s.

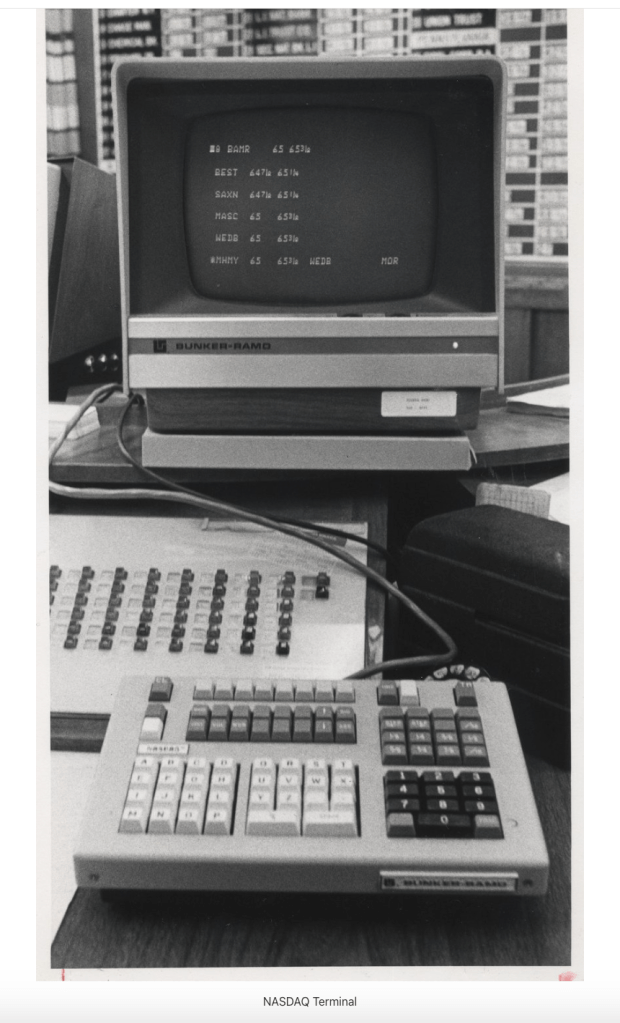

The next significant change to the stock market occurred in 1971 with the founding of the National Association of Stock Dealers (NASD) and the launch of the NASDAQ (NASD Automated Quotation) system. For the first time, computers were responsible for the execution of stock trades. The NASDAQ system was limited to the companies who listed their shares with NASD, which meant that trading was restricted to companies with smaller capitalizations than those listed on the NYSE.

electronic ticker circa 1975

With the emergence of NASDAQ, the handwriting was on the wall. Computers would soon be heavily involved in the stock market on every exchange. In 1973 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) eliminated Rule 394 which required every transaction on the NYSE be listed on the “Big Board” which meant that trading information would no longer be centralized but instead would be distributed.

The effect of the adoption of computers on Wall Street in the 70’s was largely to improve the accuracy and efficiency of traders buy/sell orders. Trades on the OTC (Over The Counter) market, prior to the creation of NASDAQ, largely consisted of handwritten orders. One academic study of the period suggested handwritten orders were responsible for errors totally over $100 million per year! An electronic method of transacting orders was therefore a welcome transition.

In the 80’s investment bankers began to shift their business focus from being advisors on mergers and acquisitions to trading. They began to use elaborate computer algorithms to find stock in the same company being traded on different exchanges at slightly different prices, sometimes as little as $0.02 per share. The computers would then automatically execute buy/sell orders with the bank pocketing the difference in the prices. This could only come about because of high-speed communication networks having access to this pricing information from different exchanges at virtually the same instant.

Wellfleet’s routers caught the interest of many investment banking firms on Wall Street because of our focus on high throughput and low delay. A desirable characteristic of our loosely-coupled multiprocessor architecture was that packet delay remained almost constant with increasing load (packet arrival rate). Tests by many of the technical groups in investment banks verified this behavior. Suddenly, our routers were of great interest to several of the largest investment bankers, not only on Wall Street, but internationally as well.

“Millions [of dollars] per millisecond” was how one early customer, Jeff Marshall, Chief Technology Officer of Bear Stearns, described the problem for us. An advantage of 200 milliseconds – 0.2 second – was enough to make a single trader wealthy. Millions of transactions per day translated into tens of millions of dollars in profits per year. Obviously, a lot was at stake for a startup company being in the middle of millions of transactions per day. Reliability was just as important as performance for routers on Wall Street.

Bob Freier was an early field systems engineer hired into Wellfleet specifically for supporting a number of investment banks in New York – Bear Stearns, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch among others. Other key accounts that Bob supported included Dow Jones, publisher of the “Wall Street Journal”, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Grumman Aerospace, Symbol Technology, and IBM’s numerous installations in the New York metro region. He had his hands full! As the number of accounts in the area grew, so did the need for more systems engineers and sales reps. Bob discovered that being a sales rep was considerably more lucrative and less stressful than the life of an SE, so he eventually moved into a sales role.

One day, Bob was out of the office making sales calls with Paul Sylvia, then the Eastern Region Sales Director. They decided to pay an unscheduled call on Bear Stearns near the end of the day. The Bear Stearns staff included: Greg Yee, a network engineer whose hobby was knife throwing, with an office door replete with a human outline target mounted on the inside; Don Henderson, an engineering manager; and Ken Starkey aka “The Bouncer”, Senior Managing Director and co-CTO who reported to Jeff Marshall. The discussion turned to some technical issues that were plaguing Bear Stearns. So, as he was often inclined to do, Paul Sylvia started sketching out some ideas on a white board, eventually declaring – as he was often inclined to do – “We can do that!”

Bob and Paul walked out the door that evening with an order from Bear Stearns for $300,000. Bob recently told me “I never had a ‘I hate going out with my boss’ moment whenever Paul was in town.”

In time, it became apparent that the selling effort was going both ways. We wanted to sell more routers on Wall Street and the investment banks that were our customers were vying for the business of taking Wellfleet public. They all recognized that we were likely to be a candidate for an IPO shortly after Cisco’s Initial Public Offering in early 1990. Wellfleet was by then second in market share to that of Cisco with approximately 9% of the total router market size of $220M growing at over 35% CAGR. The bankers thought that Wellfleet would be the next “hot” IPO so many of them were vying for our business by buying our routers.

We began to realize that in time our stock – “WFLT” – would be included in those being traded among the millions of transactions running through our routers. Oh, the irony!

Author’s Note: Jeff Marshall and I became acquainted with one another while I was at Wellfleet and he at Bear Stearns. We eventually became good friends over subsequent years. He was extremely supportive of Wellfleet and my next startup company, Agile Networks, always wanting to try the “next big thing” that I was working on.

Jeff and Bear Stearns became Agile’s largest customer. Agile was acquired by Lucent Technologies in the fall of 1996, its first acquisition after Lucent was spun out of AT&T. Jeff recognized that I did not belong in a big company, and asked me to join him on the board of Digital Lightwave, a public telecommunications test and measurement device manufacturer, in the spring of 1997.

That day, he showed up at Agile’s offices in Boxborough, Mass wearing a pressurized flight suit and carrying a sport parachute. He told me that he had flown into the airport in Stowe, Mass in his Extra EA-300 aerobatic airplane. After I gave him a ride back to the airport he said, “Stick around a little while, Willy!” So I did and he proceeded to put on a one-man airshow complete with loops, barrel rolls, inverted flight, smoke generators, the works. It was incredible!

As members of the board’s Special Committee, Jeff and I worked long hours in turning Digital Lightwave around after management had issued a restatement of its second quarter financial statements in the fall of 1997. We replaced the entire management team, and issued options to all the remaining employees. They worked hard at engineering new products and taking them to market, driving the stock price from a low of $3 per share in 1998 to a high of $125 in 2000.

Jeff and I both moved into venture capital about the same time, he with VantagePoint and me with Prism. We made a few coinvestments and saw one another frequently. After I left Prism in 2008, Jeff and I lost contact for a few years. In early 2013, I was saddened to learn that Jeff had passed away in late 2012.

Jeff was a great guy, a tough but supportive customer, a terrific pilot, a devoted father, and a true friend. I miss him every day.

Godspeed, Jeff.

Leave a comment