The first engineers started in September, 1986, the last beginning in the spring of 1987. The initial task was to create a system architecture around which the hardware and software would be designed. I had discussed this idea with Paul Severino (“the Sev”), the CEO, at some length because we did not launch InterLAN with the same approach. Steve and I knew that we had to have a solid architectural foundation for what we anticipated would be a potentially large product line developed over time. So the first wave of engineering hires was made to provide Wellfleet with the talent and experience needed to create a new class of communications systems products.

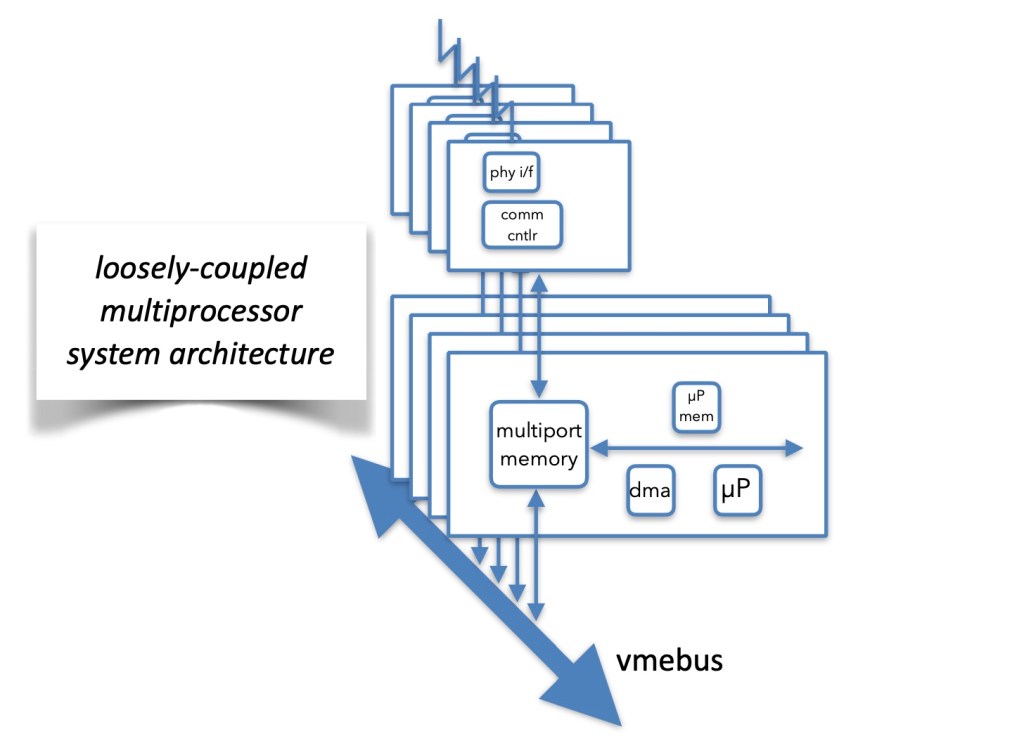

For my part, I had had in the back of my mind for some time a desire to build a loosely-coupled, symmetric multiprocessor machine, dedicated to the specific task of providing store-and-forward functionality for high-speed networks. Beginning with my work on the Antares project at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in the late-70’s, it seemed to me that such a design would be perfectly suited for distributed computer applications connected by local area networks. This was only a rough notion in my mind, I had not worked out any of the necessary details required to build even a prototype.

When we started Wellfleet, and after we were “persuaded” by Sev to design the entire first product from scratch – the original engineering plan called for using off-the-shelf VMEbus hardware in the initial product offering – it was clear to me that the loosely-coupled, symmetric multiprocessor was the right approach, even if I had not figured out the high-level design. But I knew that the first group of engineers would. And they did. I give them all the credit for creating the Wellfleet systems architecture that would serve the company for years to come.

Wellfleet system architecture – loosely-coupled, symmetric multiprocessor

Occasionally, I had to remind a few of the designers of one important detailed restriction – it was critical that the VMEbus be used like a network and not a traditional computer bus. By that I meant that no “read-cycles” go across the VMEbus. Why? Because a “read” meant that the bus could potentially be “hung” indefinitely waiting for the read-cycle to complete. This would be anathema for the system’s proper behavior. We needed to ensure that any communication through the VMEbus behave like that across a network (like Ethernet). Namely, interprocessor communication would be accomplished by sending messages through a series of write-cycles that would guarantee completion in a predictable amount of time. If we ever saw a read-cyle show up on the VMEbus in a lab test machine, we knew that we had to chase a bug – that should never happen intentionally (caveat – system startup would require a limited set of read cycles before any network traffic could be forwarded).

Wellfleet software architecture for each processor/i-o slot

Our engineers were brilliant in their architecting, design and implementation of the initial product. Led by Steve Willis and Paul Volk, they all worked incredibly long hours, unfailing in their dedication to getting the initial product out the door. They were under enormous stress to get a very complex product shipped in a very short period of time (we were not allowed to revisit the original business plan’s product development plan even after deciding to design all of the hardware in-house). I tried my best to deflect the pressure away from their day-to-day work, but in the end I failed.

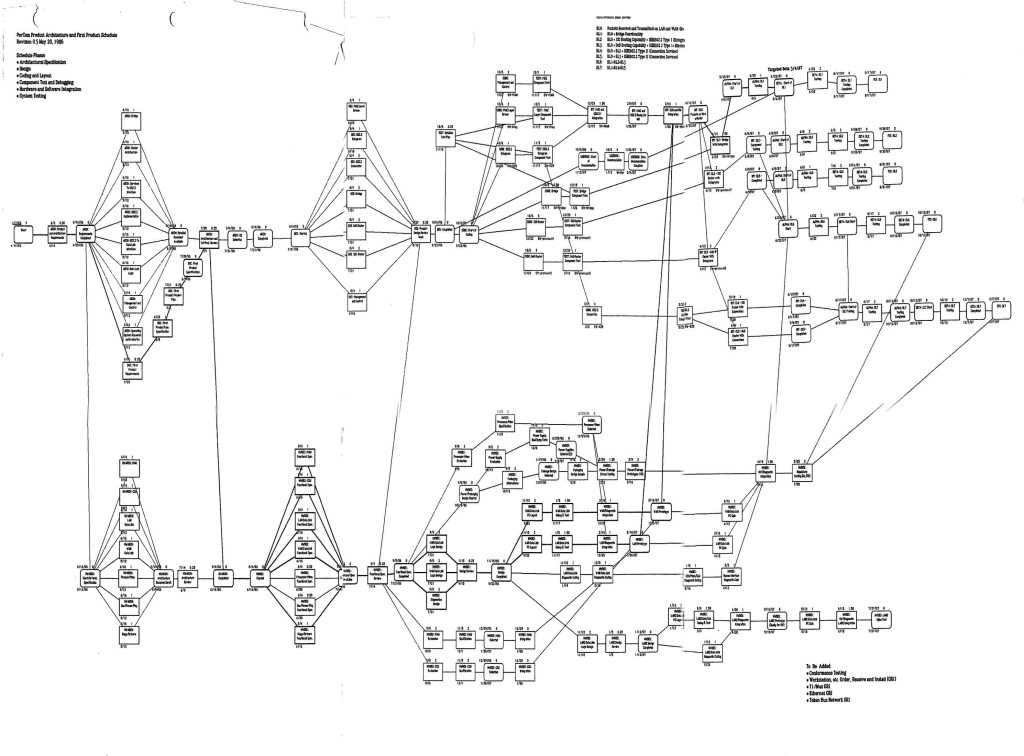

Original PerCom engineering plan Gantt Chart (courtesy Steve Willis)

The product development took much longer than the original engineering plan had called for. We had incrementally taken on a much larger task – “creeping featureism” – than what Steve and I had in mind when we constructed the engineering plan for the PerCom business plan. After we had hired the engineers and started the product architecture and design work in earnest, we never changed the original plan because we were instructed not to. I was not forceful enough in pushing back on Paul and Dave on that idea. Essentially, all of our hardware “make vs buy” assumptions were wrong, guaranteeing that producing prototype hardware of our own design would greatly delay the integration and testing of the system’s software for one processor/i-o pair, and further delay the multiprocessor integration and testing. The original schedule would in no way reflect the reality of what ultimately had to be done to produce a deliverable product.

Nonetheless, I did what I thought was my best in keeping the entire management team apprised of the actual progress of the development effort, including projecting future milestones – alpha test, beta test, first customer shipment. We started a product development board consisting of Steve, PV, a few of the key developers, and myself to bring more brainpower to the management task. Despite our best efforts, our projected milestones and completion dates all proved to be wrong. We all felt that the finish line was close but it proved to be elusive.

In the late summer of 1988, I was called into Dave Rowe’s office and informed that I would be replaced as Vice President, Engineering. He proposed that I become Wellfeet’s Chief Technology Officer, responsible for providing guidance for adopting future technologies, become a technical spokesman for the company, and support our high-level sales and marketing efforts. I was furious. I left the office before the meeting ended, and did not return for a week.

Leave a comment